What’s “critical mass” when we’re talking the level of U.S. interest rates? Maybe we should define “critical mass”. I always defined this notion as a human surprise, because it seems like it happens without notice and suddenly you’re like “what the heck just happened”? Critical mass can be good or bad, it describes a level of things that some of us hope for in goals we are working toward. What you need to know is that “critical mass” has happened in every successful business on the planet, as well as every successful career someone is lucky enough to experience. When you’ve reached “critical mass” in your life you know it. It’s when you land at a place, that place when your product or services offering has really taken off and seems to almost soar into outer space [all the previous effort on your part seems to give back in spades]. Then perhaps you achieved “critical mass”? Of course you worked hard, probably harder than anyone you know and suddenly you’re in that place you never thought or imagined would happen, a place much further than you had ever hoped… it’s that critical mass thing working for you.

Well, that’s all good but nothing much positive happens if U.S. interest rates ever reach critical mass. Any rate that a bank may charge you to borrow their money is too high right? All kidding aside, rates can get to a place where ordinary Americans will decide not to pursue the purchase of something, in the wake of [formidable] interest rates. It’s that place where ordinary Americans get to which suggests “Do Not Pass Go, and Do Not Collect the $200”, you know the place… 😉

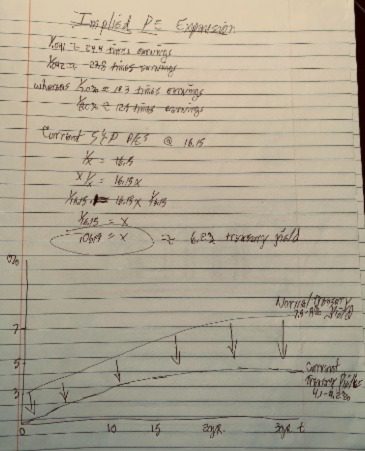

So let’s discuss “critical mass” in the world of U.S. interest rates. Back in my office days, written on my eraser board was a normal interest rate curve, climbing from left to right with the x-axis being time and the y-axis representing levels of U.S. interest rates. Below all that I placed calculations for stock price-to-earnings ratios using an inversion metric. It’s been a quick mathematical indicator for some years now to determine whether U.S. stock market valuations make sense [or not] when compared to the current level of U.S. interest rates. What you need to know is that the Federal Reserve sets and is wholly responsible for setting short-term interest rates. However, this does not hold true for rates further out [on the curve], such as U.S. Treasury bonds with maturities from 2 to 30 years. The yield on the 10-year U.S. Treasury serves as the [best] proxy for major banks to set levels on mortgage rates.

I looked in some notes I scribbled in a notebook some fifteen years ago. That’s pertinent here, the fact that I last looked at and considered my old “Implied P/E Expansion” model that long ago. Why bring it out now? That’s a good question. I think the reason I haven’t needed to consider a “P/E Expansion Model” for so long is beyond the scope of this text in so far as that’s about how long the United States had been stuck in a deflationary environment for interest rates, [until recently], as rates have been largely benign here at home. Most of that due to policy errors coming out of Washington. Now we have the opposite problem, again due to more policy errors. We’ve undergone several rounds of over-stimulus by the Federal Reserve for the better part of the past fifteen years, the only exception being while Donald Trump was in the White House. Seems like when we can’t grow our economy “organically” we employ the Federal Reserve to do the work for us? That’s so wrong! Hopefully all those stimulus and Quantitative Easing programs are in the past but I wouldn’t want to speak too soon.

The Implied P/E Expansion Model is a simple quick-test to assist in determining whether current valuations in the U.S. stock market [in aggregate] make sense given some level of interest rates. What’s funny about this is that 15 years ago I wrote that the “normal” 10-year Treasury yield was 7.5-8%! We haven’t seen that forever. You’d have to go back to the end of the 1990’s, as that yield eventually fell to sub-1% briefly during the deflationary Obama years. 🙂 By simply taking the inverse of the 10-year Treasury yield it indicates that this market, currently valued @ 18 times earnings, is not over-valued. [Ref: 1/.03034% ~ 32.96 times earnings (an approximation)]. Thus, given a treasury yield still this historically low indicates that the U.S. stock market would be considered richly valued once valuations exceed 33 times earnings, and we aren’t anywhere close to that. However, it’s now time to point out that this model has broken down, it’s not reliable in the face of what has transpired here over the past two decades. It does not take into consideration the fact that the U.S. Federal Reserve [by their numerous QE programs] have compressed and in every way, interfered with normal interest rate movements as a pure consequence of supply and demand for money. Essentially our Federal Reserve has mis-shaped, [distorted], the U.S. Treasury yield curve and now we’re witnessing the consequences of that as we speak. For example, we have inflation rates running North of 9% annually [when you exclude food and energy prices, much higher if you don’t], but the yield on the 10-year Treasury is still hanging around 3%? This is outrageous! Interpreted, this means that “real rates” or the real yield on a 10-year Treasury note is effectively -6.0%. Would you ever enter into an investment opportunity where you are guaranteed a loss? How often would anyone do that [in their right mind]? You’d be surprised as some people are still buying these notes with inflation gobbling up their 3% return each year, then taking another 6% off the top thank you very much says the U.S. Government. Crazy!

As the above photo indicates in a world where Treasury yields are climbing, the Implied P/E Expansion model will predict a stock market where valuations must shrink. [Test this model out with some lower & higher Treasury yield scenarios yourself]. The opposite is true in a world when U.S. interest rates are falling, one can expect Price to Earnings ratios to expand, or increase – this is where we were in the U.S. in the recent past. However, understand that one basic reason for that scenario was not that our economy was so strong. It was really a combination of slower growth coupled with an over-rambunctious Federal Reserve that had to over-stimulate and artificially depress interest rates constantly in order to make up for sluggish U.S. growth numbers; all due to over-regulation and the offshoring of labor, combined with the highest corporate tax rates on the planet. But by all means keep voting for Democrats – LMAO! 🙂

Fast-forwarding to today and it appears that the days of low inflation in the United States may be over. Seems like we’re about to find out what “critical mass” really looks like as far as U.S. interest rates are concerned. If you take away one thing from this discussion take away the fact that there’s nothing wrong with most of these historical economic/math models such as this P/E Expansion Model [or even the Phillips Curve]. The problem in the United States is a result of consistent “policy errors” emitting from leadership in Washington, and the bureaucrats that support them. That’s why these economic models are breaking down… In a world of 9% annual U.S. inflation, there’s no possible way [without Fed intervention distorting the interest rate market] that the 10-year U.S. Treasury would only be yielding a paltry 3%, that rate should now be at a minimum level of 10-12%!!!

I hope they are. Some links are frustrating because it doesn’t always land you to a specific page but, the main page. FOOTBALL!! I couldn’t believe the spreads!!

It takes that PhD I never earned to figure that college football thing out, especially at the beginning of any season. Who knows what a team will field?

https://www.macrotrends.net/2016/10-year-treasury-bond-rate-yield-chart

A trip down memory lane. 54 years of data suggest an even higher two year yield is needed (Fed policy and real inflation influences) to crush M2. The 10 year is more forward looking and is pointing to a contraction of significance. This has lead to a deeper inversion of the yield curve. The 2 year note, in my humble opinion needs to double, this would increase the 10 year yield in order to compete.

https://tradingeconomics.com/united-states/2-year-note-yield

The bigger question: Do we have a cap on how high we can raise rates?

You bet we do! Deficit spending never actually goes down and at today’s rates, 40% of government spending will go to JUST servicing debt by 2052 (CBO), if we raise to high, 2052 comes in 2042. These numbers don’t even include unfunded liabilities.

https://www.pgpf.org/analysis/2022/07/higher-interest-rates-will-raise-interest-costs-on-the-national-debt

PE ratios: I use Shiller, a.k.a.CAPE/PE10, this cyclically adjusted ratio is based on 10 year periods and is 85% correct since 1975 (anticipated rate of return).

https://www.thebalance.com/

Bottom line! We need to:

1) stop printing money

2) reduce spending (not just slow spending growth)

3) become regulation friendly

4) stop ESG

5) close the border (an economically strong America is where people want to come, we can’t afford them now). America first.

Your comment above was waiting in a que for me to approve, probably because you included links in here. I think there’s a setting in order to avoid future spam links. I went ahead and approved it, I trust that your links are clean? 🙂